If you can’t see the problem, there won’t be a problem. Some nuances of technique are difficult to detect if you aren’t looking for them, but they can make a huge difference in how much weight ends up over your head. One important nuance is when and how to open the torso, and this is where the “jump” cue can cause havoc.

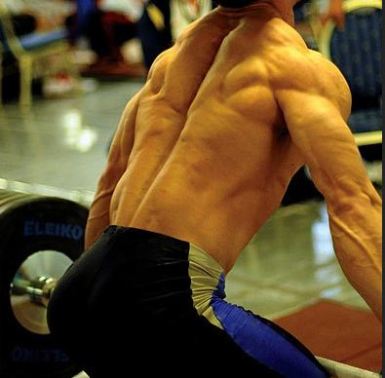

In the photo above, Kat Lee of Rubber City Weightlifting is in the vertical shin position that good lifters strive to hit when sweeping the bar off the floor. The bar is just above her kneecap, her weight shifted slightly to her heels, her shoulders a bit in front of the bar. Draw a line straight down from the end of the bar and notice where it is over her base; it is right over the instep strap, or dead center. Given that the lifter has reached this point on good shape, where we go from here can in large part determine the fate of the lift. If the lifter has learned to finish this pull with the “jump” cue, they will leave their shoulders over the bar and drive their hips forward, up and under the shoulders. The picture below exaggerates this a bit, but for a lot of lifters, not by much.

The bar is still over her base, but the position in which she’s left herself, it won’t stay there long. If she’s going to “jump,” she has to get up on the balls of her feet. That means her hips continue to travel forward to get under her shoulders and drive up. The finish, far too often, looks like this:

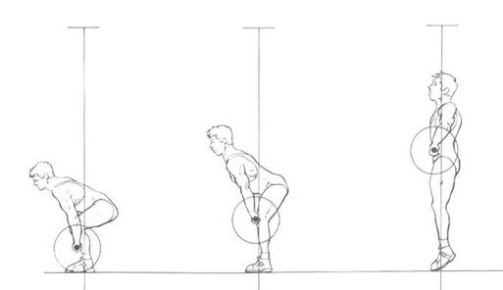

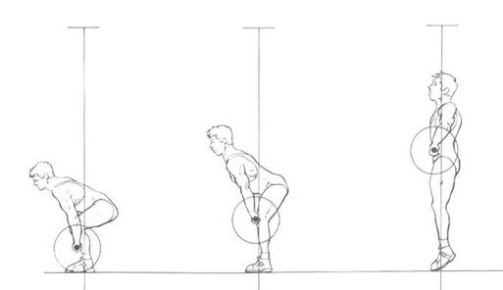

If you jump forward in your lifts, and you check yourself on video frame by frame, you’re going to find some version of this position. Again, draw a line straight down from the end of the bar. For lifters who “jump” the bar will often be out in front of the ball of the foot, or at best over it. Even at that it is too far out front. That was once considered ideal, as this is still found in textbooks sometimes:

There is not a single world class lifter who does this. None. But I still see the illustration below being passed around, part of a series of stills demonstrating “correct” technique. The bar is at mid-thigh, but the shoulders are still over the bar and the heels already off the ground.

If you follow through as this series of pics suggests, You can still extend up and behind the bar as you should, but even in this instructional pic, notice where the bar is–too far away already and moving away from the lifter.

So what should we think if not jump? Stand up. Just stand up. From the bar position just above the kneecap, instead of leaving your shoulders forward and driving your hips forward to the bar, simply stand up and watch the bar come right back to your hips. (Or upper thighs in the clean)

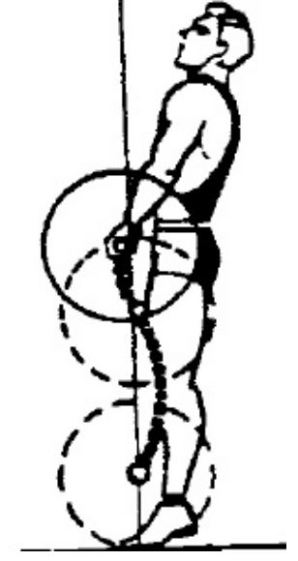

In the photo above, Kat is beginning to raise her torso, thinking “stand up” rather than jump. The bar continues to track backward, deeper over her base, rather than being driven forward. Below she is near the finish of the pull, bar still over her base, her torso nearly vertical over the back half of her foot.

From the above position she’ll extend up and slightly back to finish the pull. Now, I can hear the howls of protest now, “How can you just stand up and get any upward momentum on the bar at all. That’s just a deadlift!” No, it isn’t. It’s just a deadlift if you do it slowly. As you may know, we don’t do an Olympic lift slow.

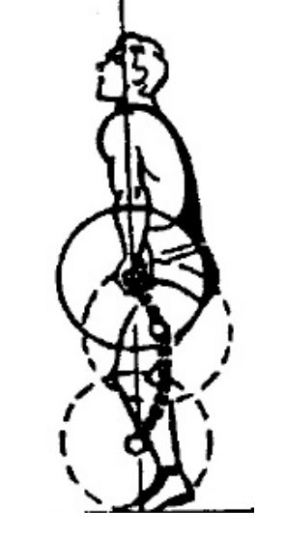

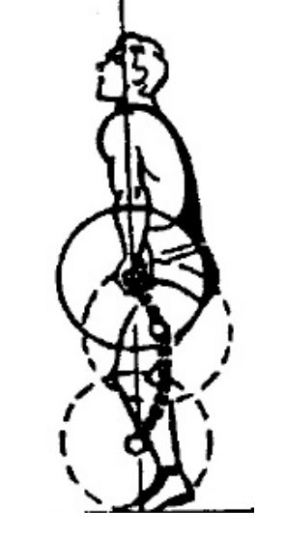

If you’ve been in the sport for a even a little while, you’ve no doubt heard of the double-knee-bend. The knees extend in the first pull, then as the torso extends in the second pull, the knees flex again, pushing forward under the bar. This is supposed to happen automatically, and it does if you focus on extending the torso. The two strongest muscles in the hamstring group cross both the hip, where their job is to extend the hip, and the knee, where they act to flex the knee. With the bar just above the knee at the end of the first pull, the hamstrings are stretched near to busting and ready to fire. When you attempt to rapidly extend the torso–that is, stand up–the hamstrings flex hard to extend the hip. But they are also flexing the knee and, if you do it right, you end up here:

and very shortly thereafter, here:

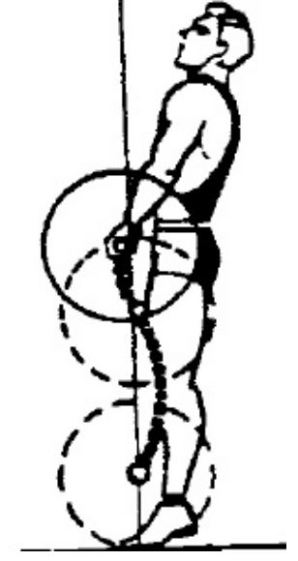

The double knee bend happens automatically; so too, I believe, the initial drive upward from the quads. That upward drive can and should be emphasized. How? Think stand up, punch up. Or punch hips up. Or punch feet down. Anything that gets you driving your hips up with your legs.

Pulling this way keeps the double knee bend short and sharp. It puts you just a little out of balance backwards and forces you to withdraw your hips before they can drive too far forward. You’ll end up jumping backward and inch or two at most.

So the lesson is this: Do not jump up. Stand up. Then pull down. Stand-up, pull-down. If you can get yourself doing that, the rest is cleaning up details.