Patience

As important as it is to have patience with the process of mastering the sport of weightlifting (or for the eccentricities of your coach) the specific use of “patience” to which I refer here is waiting for the proper power position before forcefully engaging your legs in the upward drive phase of the “pull.” Once an athlete is able to consistently execute the snatch and clean with good technique, “patience” is by far the most common cue I use. (My athletes have threatened to write all of my synonyms for patience and its increments on the gym walls: wait longer; a skosh; a bit; a nanosecond; a fraction; one more inch; three fifths of a second, etc.) This kind of patience is, however, vital to making heavy lifts consistently. If there is one error still common even in intermediate and advanced weightlifters, it is lack of patience to the power position.

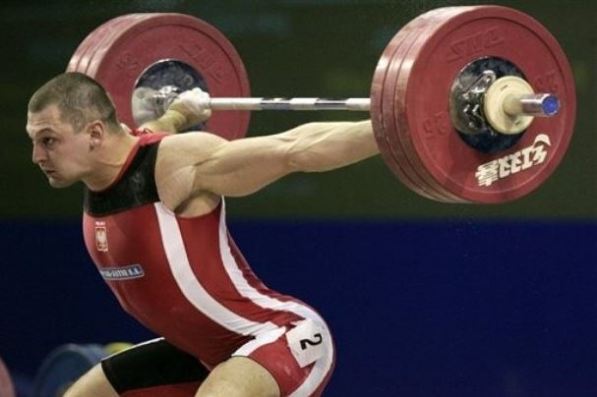

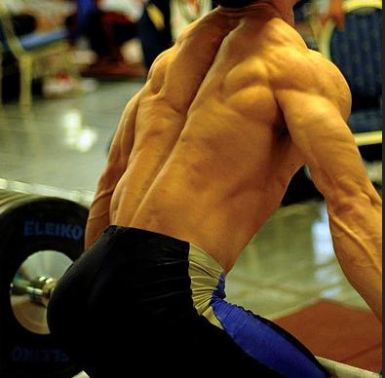

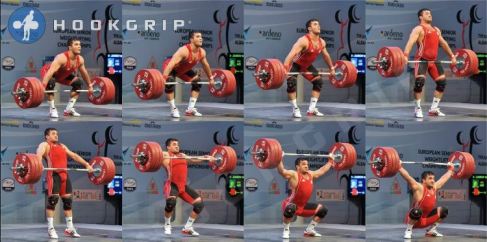

So what is a good power position? I think most coaches–weightlifting coaches, anyway–agree it is where the torso angle has opened to vertical or near vertical, knees are bent with the quads loaded for the leg drive up, and the heels are down, with balance at the middle of the feet. (Please excuse the blurry pics. My lifters are just too fast? No, I have a shitty camera on my old iPhone 5s)

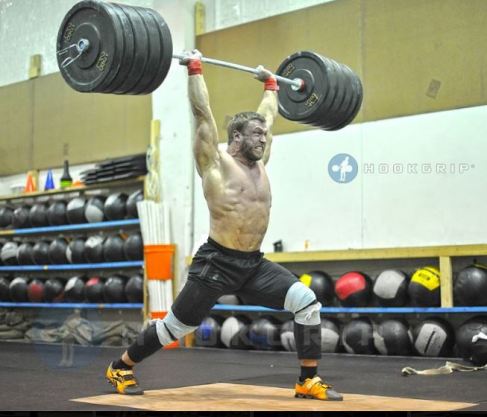

Patience means waiting for this position before you trigger the leg drive upward. If you hit this vertical torso power position, with shoulders slightly behind the bar, your chances of keeping the bar close in the move under the bar improve dramatically. Your interaction with the bar and timing of the pull under are enhanced as well.

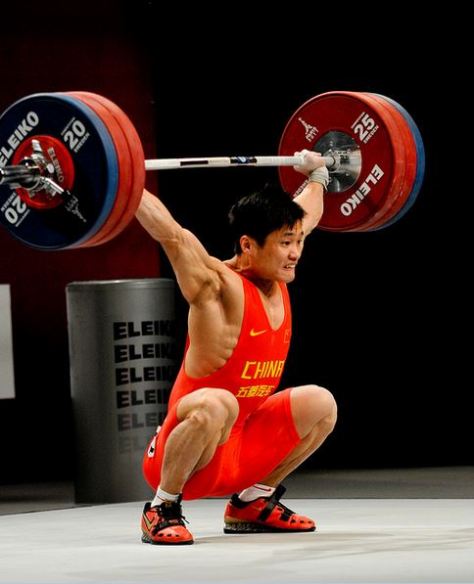

One of the reasons that competing early and often is important for developing weightlifters is to learn this patience under meet conditions. The extra adrenalin engendered by competition makes lifters far less patient to the power position. Rushed lifts are the very essence of “newby.” The lifter must learn to control the extra energy and channel it into proper technique on the competition platform. If they do, that extra energy can mean PR lifts. If not, it’s missed openers and bomb-outs. So where does the lifter go from here? If you hit the power position properly, the top of your pull should look something like this:

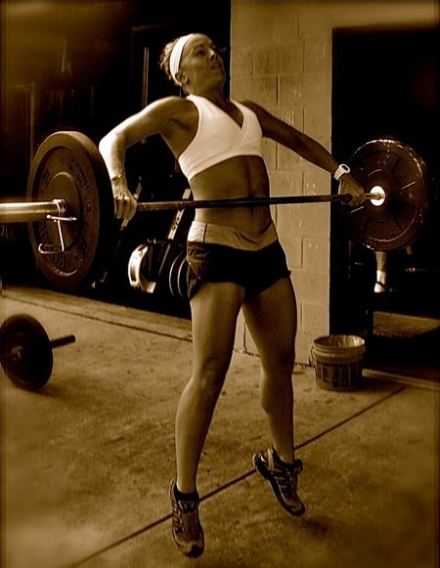

But how does a lifter learn this kind of patience? The best drill we have used is a variation of the No-Feet Drill popularized by lifters like Nork Vardanian. The way I have modified the drill is to have my lifters keep their heels down through the entire lift, their full foot glued to the platform as they do the lift, usually a power version. This has two beneficial effects: first if forces them to wait for the right power position, heels on the floor right through the upward leg drive; second, it reinforces good timing in the move under the bar by forcing them to begin moving down immediately upon full extension of the knees and hips. If you have used a jumping type drill to teach the explosive leg drive portion of the lift, this is especially helpful in counteracting the tendency to linger at the top of the pull that the jumping drill may ingrain.

A couple of notes:

I and Rubber City Weightlifting have moved to Unrivaled Strength and Fitness in North Canton, Ohio. Rubber City Weightlifting now has the company of highly ranked powerlifters and a great powerlifting coach, Justin Oliver. Travis Sholley handles the CrossFit coaching. I love having all the barbell sports under one roof. We weightlifters can live in our bubble a bit too much, sometimes.

RCW welcomes visiting lifters and coaches, so if misfortune should strike, and you find yourself in Northeast Ohio, drop me a line at danielfbell56@gmail.com and we’ll get you in for a visit or training session.

Also, I’ll be writing for myself again, as my deadlines seem to be the only ones to which I can actually stick.