Yeah, You Should Deadlift

You don’t have to spend much time in the sport of weightlifting before you understand in your bones the importance of squatting to your success as a weightlifter. In every training hall you’ll hear discussions of programs and impressive back squat weights, on weightlifting message boards every conceivable permutation of squatting programs are dissected and argued. There are nearly as many youtube videos of world class lifters back squatting as there are of them doing the lifts. The message is clear: squat or suck. What I almost never hear is anyone (besides Don McCauley) mention the importance of the deadlift to successful weightlifting.

For some reason the deadlift gets short shrift in weightlifting. Coaches and lifters are always trying to substitute pulls in their programs and refer to them as “strength building” exercises. Bullshit. Pulls–the bastard hybrid of deadlifts and weightlifting’s full lifts–have been rightly rejected by a lot of good coaches because they do not duplicate the speed and technique of a classic lift, but are not heavy enough to really improve back strength or, to a lesser degree, hamstring strength.

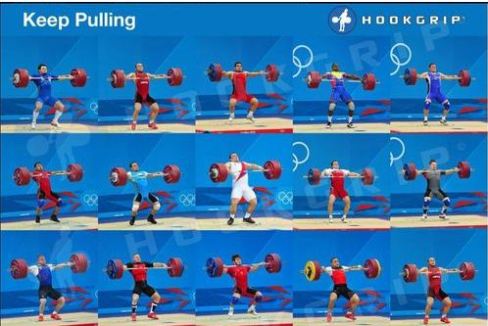

“But won’t heavy deadlifts make my pull slow?” No. Hell no. Did you ever see anyone fly out of the hole with a new PR single in the back squat? Did anyone ever say that squatting that heavy makes a lifter slow? No, because we’d all look at that person as if they were the dumbest person in the room. Back squats make you STRONG and strong matters in weightlifting.

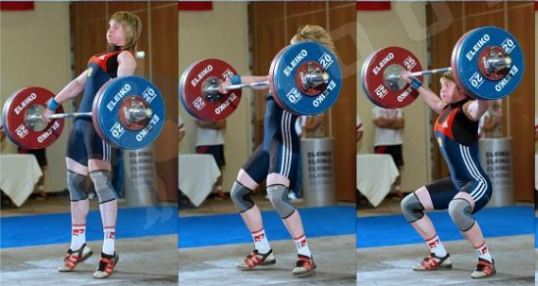

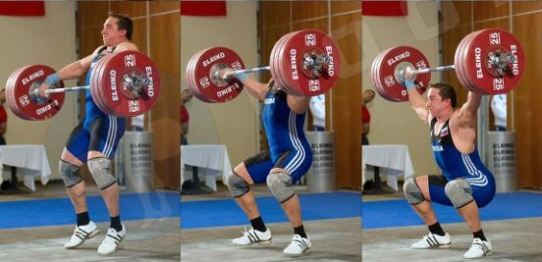

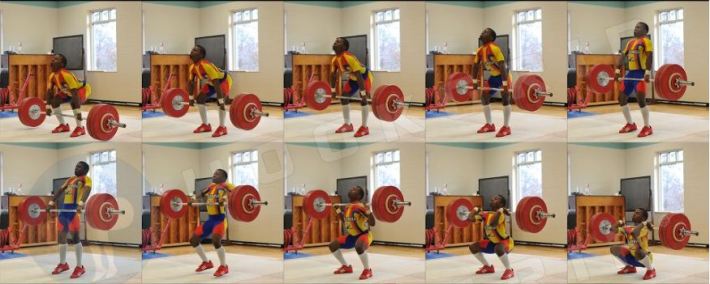

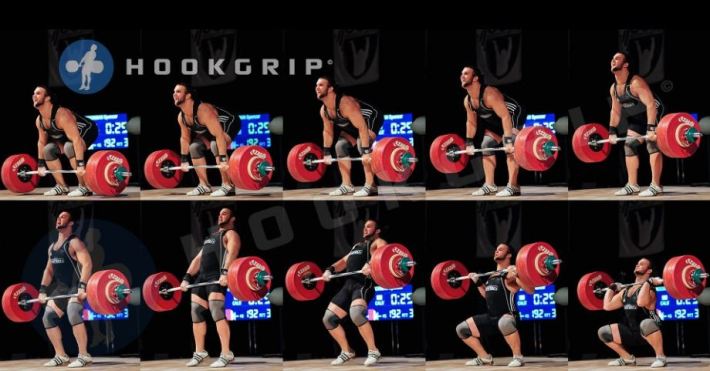

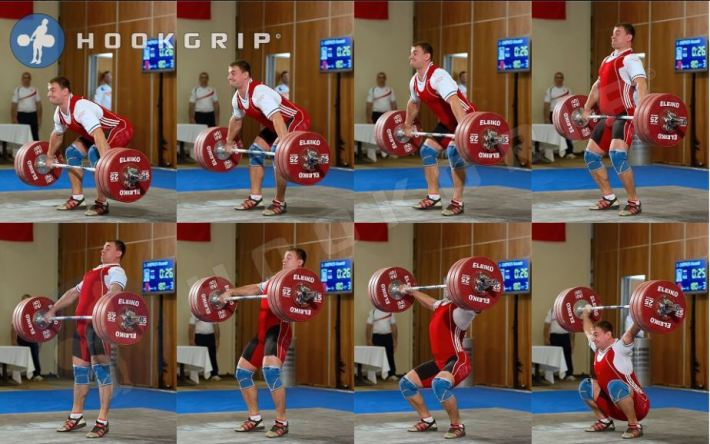

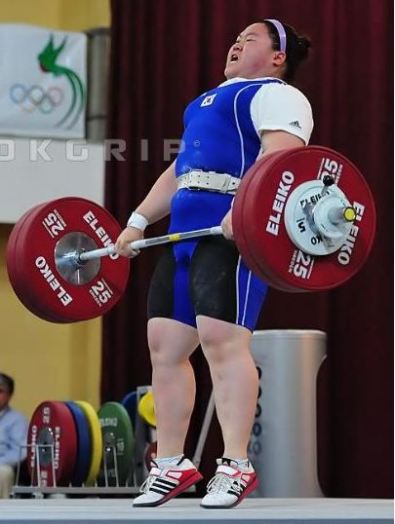

Deadlifts make you STRONG, but they also do a few other good things for you. Early in a lifter’s career, deadlifts teach proprioceptive awareness of the “locked down” back position so important to the classic lifts. The spinal erectors, lats, all the small muscles around the shoulder blades and the core have to be properly contracted and held in that position throughout the pull. The lifter has to feel that to hold it. Deadlifting with precise form teaches the lifter to feel that position and, more important, hold it while moving. Early on I never have a lifter do deadlifts with more weight than they can hold perfectly for a triple. As holding that position becomes ingrained habit, the weights can start to go up.

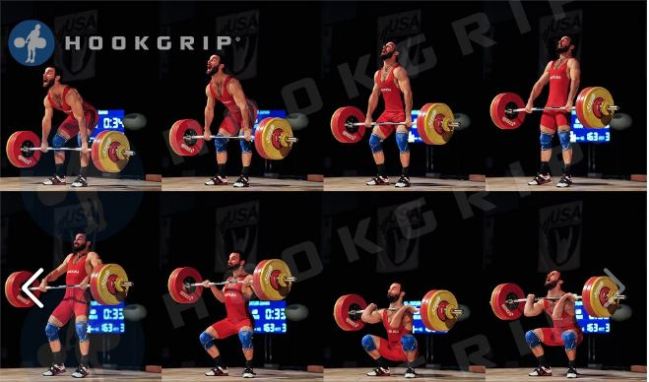

Deadlifting as heavy–as heavy as good back position and technique allows–also teaches lifters how to strain. Someone new to lifting does not know the limits of their body. The mind says “heavy” at far lighter weights than the body can actually handle with decent form. Deadlifts teach a new lifter to strain against a weight and stay with it better than any exercise I’ve used.

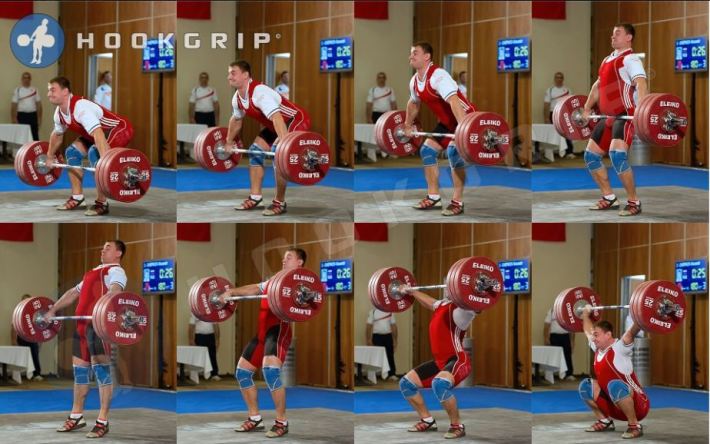

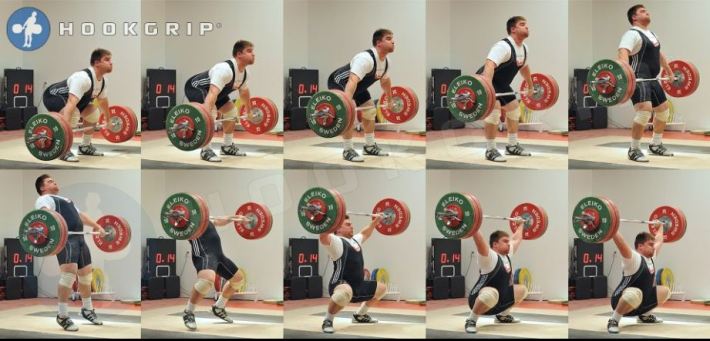

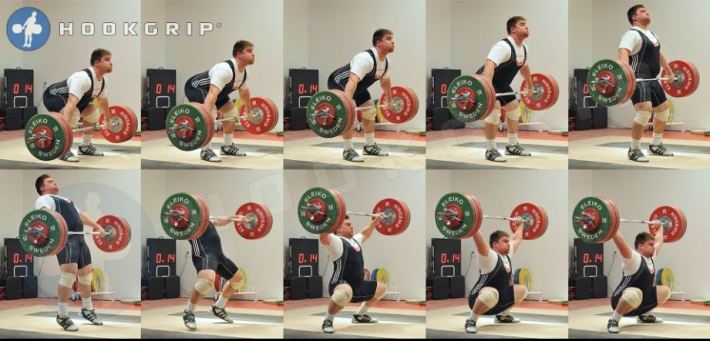

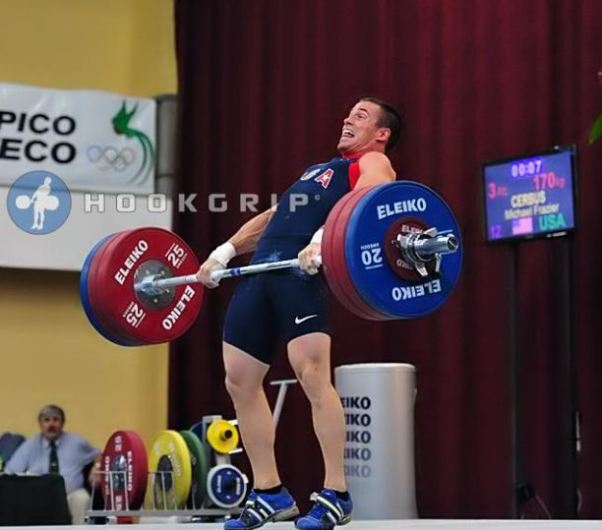

I can hear the protests now. “But heavy deadlifts will mess up the technique of the classic lifts!” I didn’t say powerlifting deadlifts, did I. Deadlifts for weightlifters should all be done with exactly the same form as a pull, but heavier and necessarily slower. Above the knees the lifter should simply stand up over his or her heels, attempting to push the hips as high as they can. I have a couple lifters who even “pop” their hips up at the end.

How heavy is heavy for deadlifts? I don’t see a reason to go over 125% of a lifter’s best clean for much of the year. My more experienced lifters are usually working between 105% and 120% for triples. They do this once a week and alternate clean and snatch deadlifts, one week CDLs and the next SDLs. If it’s far out from a meet and the classic lift volume is not high, they can go for a big single or double.

I had a 94 kilo lifter visit a few months back who could pound out sets of five with 225kg in the back squat, but his back gave off the floor attempting a 125 snatch and 165 clean. I had him start deadlifting to teach him how to better hold back position off the floor and make his back stronger. His back position quickly improved and he just recently hit a PR 131 snatch and PR 172 clean. He always had the leg strength to do those lifts, but lacked the back strength and proprioceptive awareness of his back position to hit them.

Deadlifts will not make you slow. They will make you strong. And as grandpa used to say, “It’s good to be strong.”